Strength and Conditioning From A Clinical Perspective

Strength and conditioning is a major component of pre-season and in-season training. Strength and conditioning, if done properly, can help minimise injury risk AND improve performance. Upon reading this article, you should develop an understanding about what strength and conditioning is from a clinical perspective and the benefits of receiving it from an osteopathic or physiotherapist point of view.

What is Strength and Conditioning? How does this differ from other training?

First, let's start with some definitions. We define strength as “the ability of a muscle/muscle group to develop maximal contractile force against a resistance in a single contraction.” Secondly, we define conditioning as “interventions to elicit improvements in elements of performance or function.” When these two terms are combined, we are hoping to improve muscle capabilities which then lead to improvements in performance. This doesn’t just mean sporting performance, but also functional performance. People who suffer from osteoarthritis and want to be able to walk their dog, are likely to require strength and conditioning within their management program. Just as a footballer who is wanting to have a high quality season requires strength and conditioning to improve performance, and also minimise injury risk.

There are various categories of muscle training and development that sit under the umbrella of strength and conditioning training. These are other terms you may have heard like power, endurance and hypertrophy (or what some might call bulking up). To train these other elements, there are differences in load, intensity and repetitions which make training more specific to these categories. But they are different from strength.

Power is defined as “the highest output attainable during a particular movement.”

Endurance can be looked at in two ways. The technical definition is “the ability of a muscle or muscle group to repeatedly exert sub maximal force.” Or a more simple way to think about endurance is the ability to perform a specific muscle contraction for a prolonged period of time.

Muscle hypertrophy is the “enlargement of overall muscle mass and cross sectional area.” The growth of muscle.

Strength and conditioning training focuses on training these areas specific to the patient’s needs. For example, a patient that has one large step at home, might not have the power to go up and over this step, so this patient will require training in the power category. Another patient might struggle with carrying heavy timber from one part of the worksite to the other, and this would fall more into the strength category, and focusing on building strength for this patient. An endurance related issue might be a runner who fatigues in their hamstrings towards the end of a marathon. Finally, a hypertrophy related scenario might be a difference in muscle bulk between a patient’s quadriceps muscles on either side, so the focus would be to build more symmetry here.

There is usually crossover between these categories in training, which is good! You can train strength and see improvements in power, and you can train power and see improvements in strength. Same goes for endurance and hypertrophy. But you will see the most benefit in the category your clinician is trying to train and improve, as that is identified as the area of need for you.

Does Strength and Conditioning Minimise Injury Risk?

There has been much debate around this question for a number of years. Some studies have demonstrated that strength and conditioning will not minimise injury risk while others have displayed it can. What’s important is to look at what programs some of these studies implemented, and whether they are actually targeting “strength.”

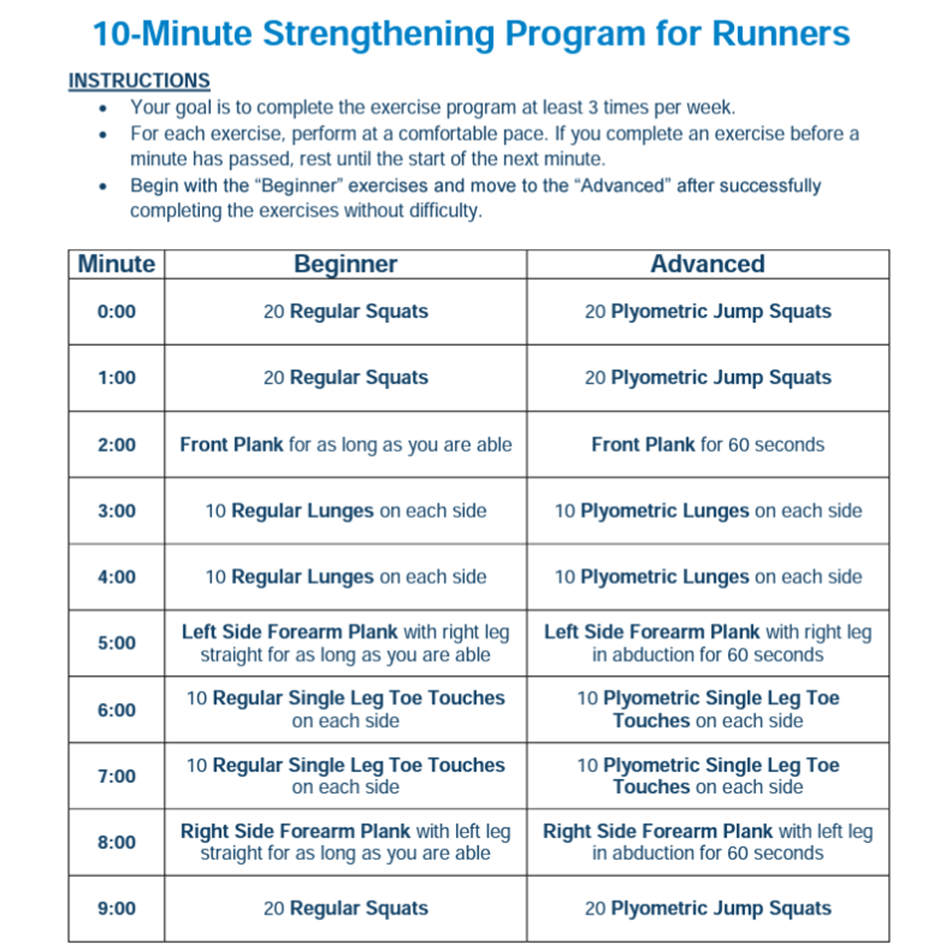

For example, one study looked at marathon runners and investigated how a strength program would influence injury rates and performance. They implemented a program structured like this:

This study found that this “strength” program contributed to no significant decrease in the injury or improvement in average finishing time in marathon runners. However, some clinicians have heavily scrutinised this program due to the fact it doesn’t address a whole bunch of factors involved with strength training. For example, there is no mention of intensity. How fast are these athletes performing these movements is unclear. There is no specificity to the exercises either. Athletes will differ in their strength deficits, which leads to the next point. There is no real progression criteria that is specific to each individual either. This can be seen at the plank, where the patient is asked to plank for as long as they can hold it, and then progress to a minute hold. But what if that patient can already hold for 55 seconds on their first try? Holding for a minute might become easy after a few sessions, and if there are no progressions from this point on, how will the patient's strength develop? The answer is, they likely won’t, which is why I and others believe this study had the results it did.

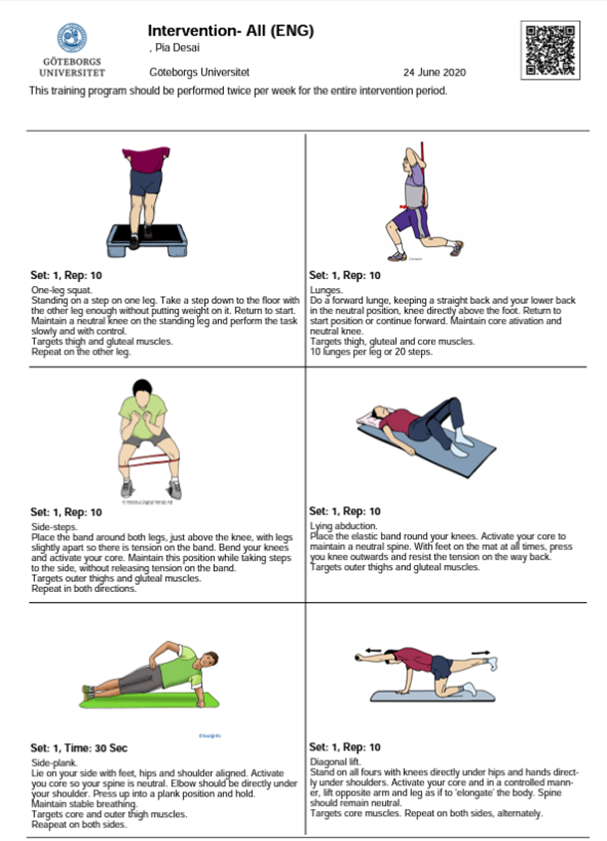

Another study utilised a program that looks like this:

(Desai et al., 2023)

While this program is an improvement on the previous one, it still isn’t a very good strength program. However, even with just a few improvements from the other program (some resistance based load using a band, step up resistance) this study displayed positive results in runners, as it found that those completing this program were found to be 85% less likely to sustain an injury (2). A program that is more tailored, more strength focused and specific in its intensity, load, etc, should enhance the avoidance of injury, and also improve performance.

You might also live longer, if you’re stronger?!

A quick side note before we continue on with how to structure a program, but having healthy muscle tissue from strength training has shown to influence longevity. A study on all-cause mortality rates found that low muscle strength was associated with an elevated risk of all-cause mortality, indicating muscle strength as an important predictor of health outcomes for older adults (3). Interestingly, there was no relationship identified between muscle mass and mortality. So even if you have more muscle in your body composition than the average person, if there is no strength behind it, it potentially has less health benefits.

How to structure your program!

Structuring a program for each individual will be different depending on their goals, lifestyle, sport, injury history and equipment available. These are all factors that differ between individuals, so it is difficult to give a set program that will be suitable for each person. Each program will need to consider the following.

- Intensity

- Repetitions

- Sets

- Load

- Frequency

- Rest

For strength training, there are general principles to follow in regards to the factors above. Intensity for strength training is very high. To train strength and improve, you need to work hard and put in maximal effort into the repetitions you perform. It shouldn’t feel easy, it should feel challenging and work up a sweat! The ideal number of repetitions seems to differ, depending on what you read out there. To get the most out of strength training, the ideal repetition and set number is between 4 sets of 3-10 repetitions. Research has suggested that to get the most out of your training, training at a 3-5 repetition maximum (the most you can lift 3-5 times) is where you can get the most out of strength training (4). The load will change between individuals depending on their 3-5 repetition maximum, so this can be assessed by your clinician. The frequency of training is ideally around 2-3x per week. Studies have shown that around 25-45 reps per week of exercise has the most benefit (5).

When to See Your Osteo or Physio!

The key here is not to wait till you're injured. The best time to see your clinician is at the start pre-season, throughout pre-season and in season. This is because baseline measurements can be taken at the start of pre season, and be assessed throughout pre season and in season to ensure you are always at an optimal level functionally to minimise injury risk. It doesn’t mean that you won’t suffer an injury, but it allows for the management of future injuries to be managed more effectively, and lead to a quicker return to on field sport.

Measurements that are taken are of not only strength, but also aspects of function like mobility, endurance, power, etc. For example, at the start of pre-season, an athlete might be able to leg press 65kg on their right leg, and 75kg on their left leg. By the middle of pre-season, the individual can do 75kg on both. Then, let's say by round 6 in their football season, they start to notice their right hamstring is a bit tighter than usual, a bit sorer and they aren’t playing as well as they were weeks prior. The clinician then assesses the athletes leg press, and they are at 60kg on their right leg and 70kg on their left leg. This can be an indicator that this person is being overloaded, they are dropping off their strength at the gym, and changes need to be made. This process is easily achieved with measurements before and during pre-season, and then being monitored via in season assessments.

The Take Home Message….

If you are interested in taking your training, sport and health to the next level, then you should come and see the clinical team at Peak MSK Physio. We thrive from seeing people reach that next level in their training, want to give individuals the best chance at reaching their goals. Whether it be beating that 5km personal best, playing better football or wanting to walk just that bit longer, we can help you.